The "Capability Overhang" of AI in Distributed Care

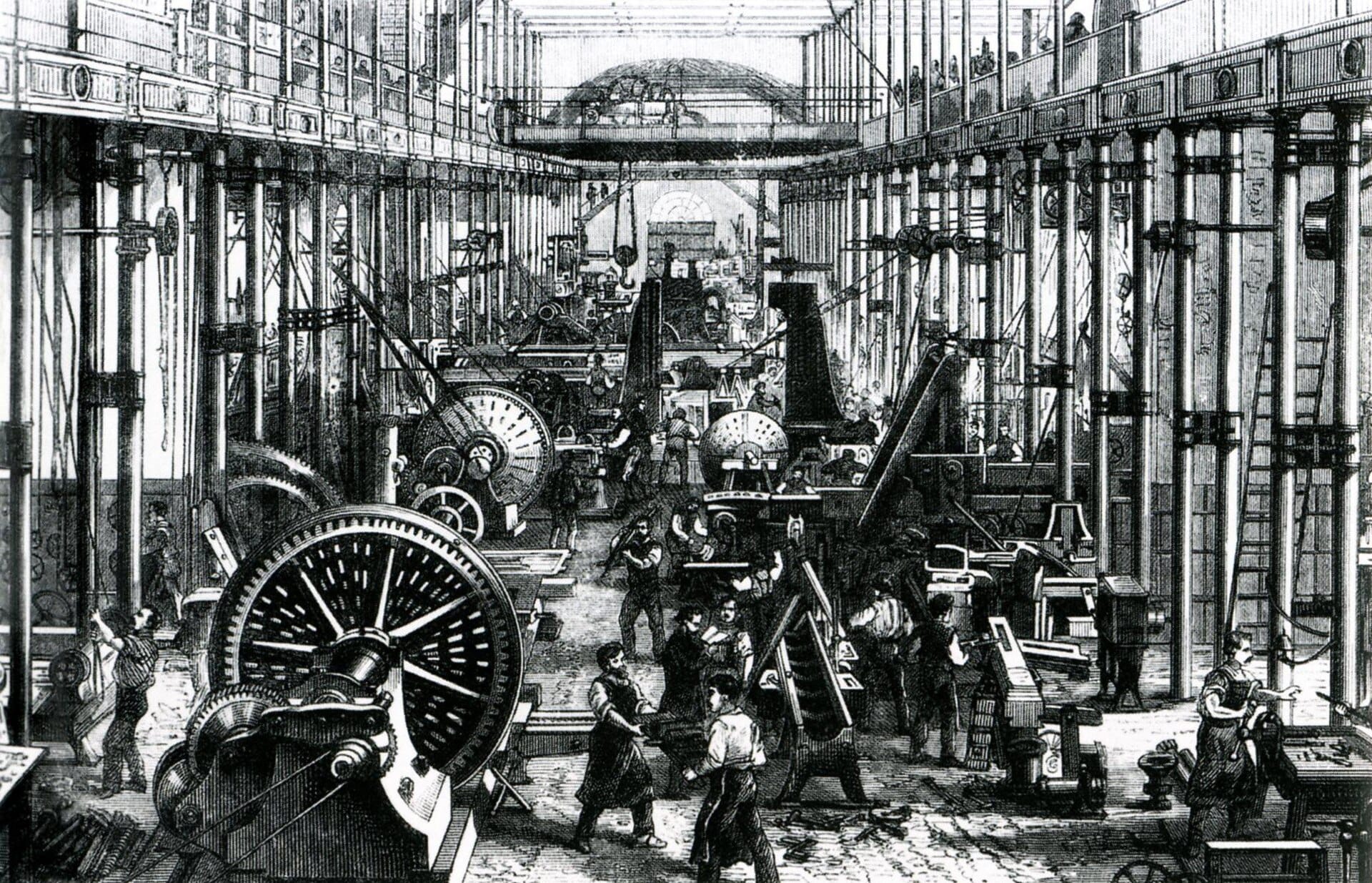

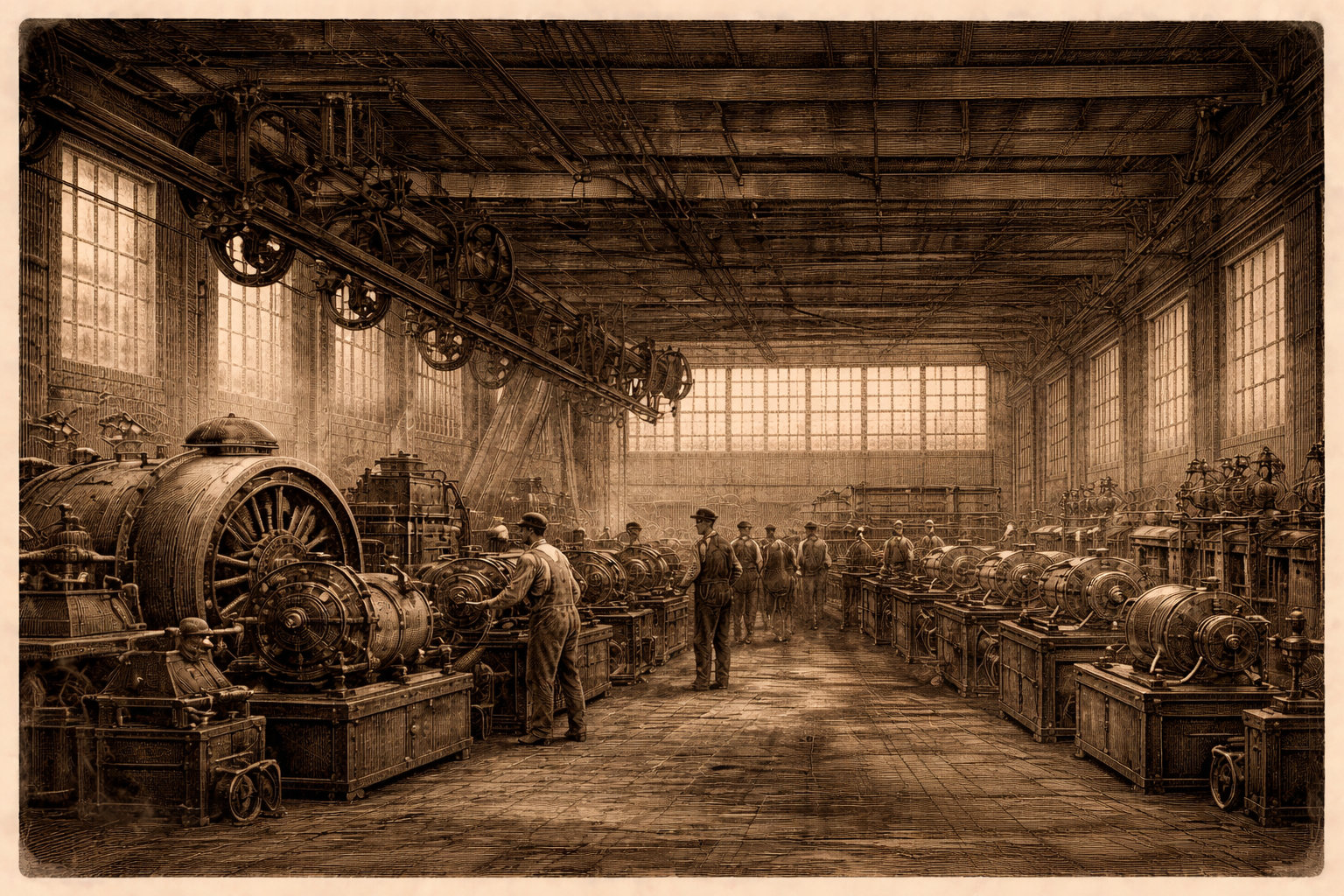

In the early 1900s, American factories electrified.

Owners spent enormous sums ripping out steam engines and installing large electric motors. The upgrades were expensive, visible, and widely celebrated as modern. And yet, productivity barely moved.

Economists later called this the “productivity paradox,” but there was nothing paradoxical about it. Factory owners upgraded the power source without upgrading the system. They treated electricity as a better fuel rather than as a new architecture. The layout of factories remained centralized. The workflow assumptions remained intact. The org charts did not change.

They swapped the engine but kept the carriage.

The real productivity gains arrived only when operators asked an uncomfortable question: If electricity allows power to be distributed, why is the factory still organized around a single source?

When smaller motors were attached to individual machines and production lines were redesigned around continuous flow, output surged. Electricity did not create the productivity boom. Institutional reorganization did. But why did it take operators so long to figure this out?

There is a new name for this dynamic, doing the rounds in the AI world: Capability overhang.

A capability overhang appears when technology advances faster than institutions evolve. The power exists, but the structure around it remains anchored to older assumptions. Value accumulates in the gap between what is possible and what organizations are willing to reorganize around.

Distributed care is sitting in that gap right now.

The Capability Overhang of AI in Distributed Care

Most distributed care agencies are organized around functional silos. Recruiting fills seats. Scheduling fills shifts. Compliance reduces risk. Retention is reviewed quarterly. Each department has its own tools, dashboards, and leadership. Each function optimizes locally.

This architecture made sense when software was narrow and brittle. Systems handled discrete workflows, and humans were required to coordinate across them. The organization mirrored the limitations of the tools.

But AI no longer shares those limitations.

AI systems can track engagement across time, identify churn patterns, correlate schedule volatility with callouts, and surface risk before it manifests as attrition. They can coordinate communication across recruiting, onboarding, and staffing without requiring a human intermediary at every step.

And yet, most agencies are still deploying AI in fragments. They use it to accelerate outreach, improve reminder systems, or automate compliance nudges. These are incremental improvements layered on top of a fragmented architecture.

It is the modern equivalent of installing electric motors while preserving a steam-era floor plan.

Patients and caregivers do not experience an agency as a collection of departments. They experience a single relationship that unfolds over time. The first recruiting or intake message shapes expectations. The onboarding process establishes trust. Early scheduling patterns influence income stability. Schedule volatility increases stress. A last-minute callout reshapes an entire week.

From the patients' or caregivers' perspective, this is one continuous journey. From the agency’s perspective, it remains divided across functions.

That fragmentation carries real economic cost.

- Early caregiver churn that forces repeated recruiting spend

- Schedule instability that increases callouts and overtime

- Lost referrals due to inconsistent coverage

- Compliance friction that slows time to revenue

A Redesign Moment: "Recruit to Retain"

AI makes coordination cheaper. But true coordination does not fit neatly inside a recruiting department, a scheduling team, or a compliance function. It challenges the premise that these should be separate domains in the first place.

If agencies are serious about optimizing the patient and caregiver journey end to end, roles will need to change.

Today, recruiting is rewarded for volume. Scheduling is rewarded for coverage. Compliance is rewarded for documentation. Operations is rewarded for firefighting. Each function defends its metrics. No one owns longitudinal stability.

In a Recruit-to-Retain model, the unit of performance shifts from task completion to journey integrity.

The head of recruiting is no longer measured solely on applicants generated, but on early-tenure retention and stability of hours within the first 60 to 90 days. Scheduling is not evaluated purely on shift fill rate, but on volatility reduction and caregiver continuity. Compliance is not a reactive policing function, but an embedded signal system that surfaces friction before it turns into risk.

In this model, AI does not sit inside each department as a productivity tool. It operates across the lifecycle as a coordination layer. It tracks caregiver engagement from first outreach through ongoing staffing. It identifies instability before it shows up as churn. It aligns patient demand with caregiver preferences in real time. It reduces the number of handoffs that require human reconciliation.

Humans do not disappear. Their work changes.

Coordinators move from being manual routers of information to exception managers who handle edge cases and high-empathy conversations. Recruiters spend less time chasing paperwork and more time building relationships with high-potential candidates. Leaders spend less time reviewing lagging indicators and more time intervening on leading signals.

The organization itself becomes less siloed and more longitudinal. Instead of optimizing a series of disconnected functions, it optimizes a continuous experience. The caregiver journey is designed deliberately, not inherited accidentally from software constraints.

This is what it means to reorganize around distributed coordination.

The Implementation Wedge

Organizational redesign sounds abstract. It does not need to be. The first step is not to eliminate departments. It is to change what is measured and who owns the journey.

Start with three moves:

- Define one cross-functional metric, such as 60-day retention combined with hour stability.

- Assign a single accountable owner for caregiver and patient lifecycle performance.

- Pilot an end-to-end model in one branch or region, not just one task automation.

When incentives shift, behavior shifts. When ownership shifts, coordination becomes real.

Agencies that do not make this transition will still buy AI. They will deploy it inside recruiting, inside scheduling, inside compliance. They will improve each silo incrementally.

They will improve productivity at the margins. But they will not change the slope of the curve.

They will preserve the architecture that produces instability in the first place.

They will install the motors.

And they will miss the redesign moment.

Kunal

Co-founder, Arya

https://www.linkedin.com/in/kunalsarda/

540-250-2633